By Robert McLachlan

As 2025 winds to a close, I am writing from the Rodney district north of Auckland – Rodney being famous as the home of the Rodney & Otamatea Times which published this banger in 1912. (Andy Revkin of the New York Times brought it to wide attention in 2016.)

The 1912 article had been rediscovered a few years earlier thanks to “Papers Past”, a project of the National Library of New Zealand to scan old newspapers, that began in 2001 and continues to this day. As for the Rodney Times, founded in 1901, it ceased publication in July this year, along with many other New Zealand community newspapers.

The “coal consumption” story itself is a caption from an article by Frances Molina in the March 1912 issue of Popular Mechanics, a model popular science article of the day. It concludes with a reflective passage that could stand today:

This rapid publication of worldwide science news was possible because New Zealand had been connected to the rest of the world by undersea telegraph cable in 1876. Other science news on 14 August 1912: the world’s deepest bore dug in Silesia at 7348 ft; nickel kitchen implements; how camphor is made; a skipping machine which turns the rope and counts your skips (I can see that being a winner today); a Swiss proposal to build a tunnel linking the Black and Caspian Seas (an idea that reappeared in 2025); and (this one is real genius) a way of preventing buckets of water spilling on trains, namely a wooden lid.

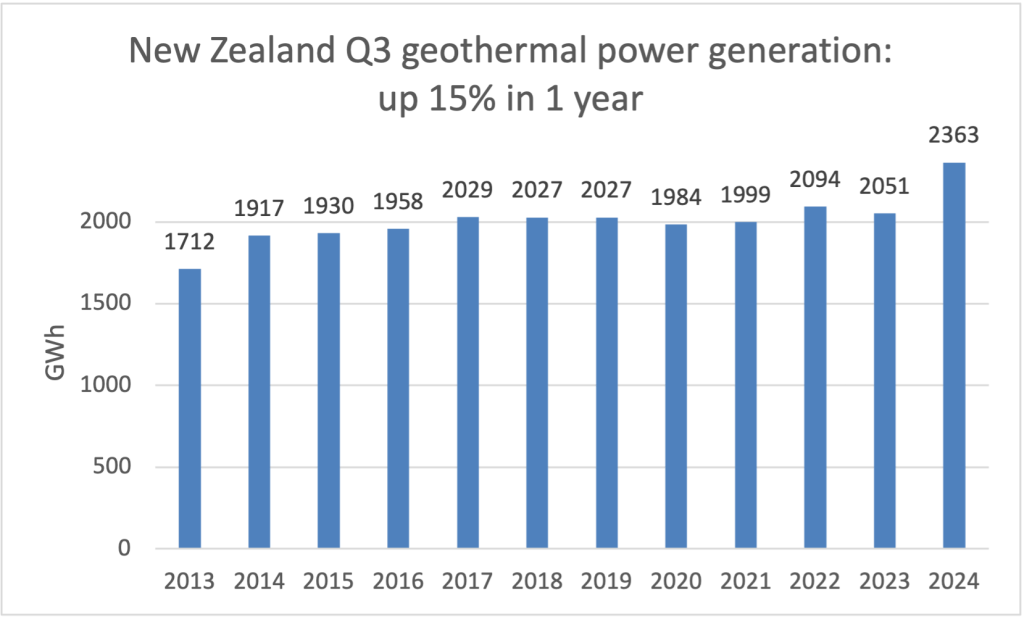

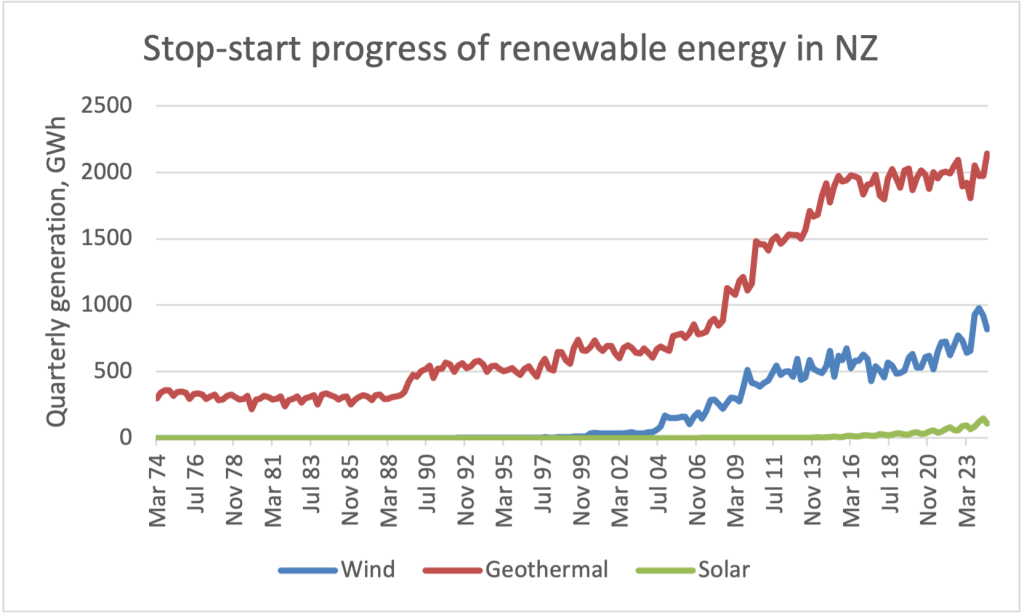

I dabble a little in social media and, in my experience at least, what fires engagement is not outrage but good news, like New Zealand showing a possibly record-breaking run of days with zero coal- or gas-fired electricity:

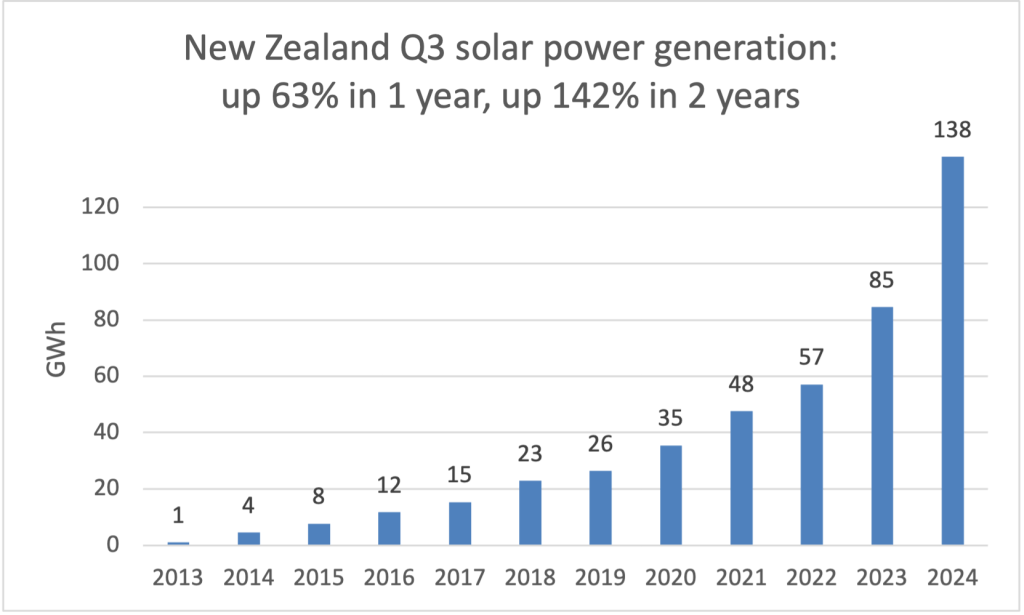

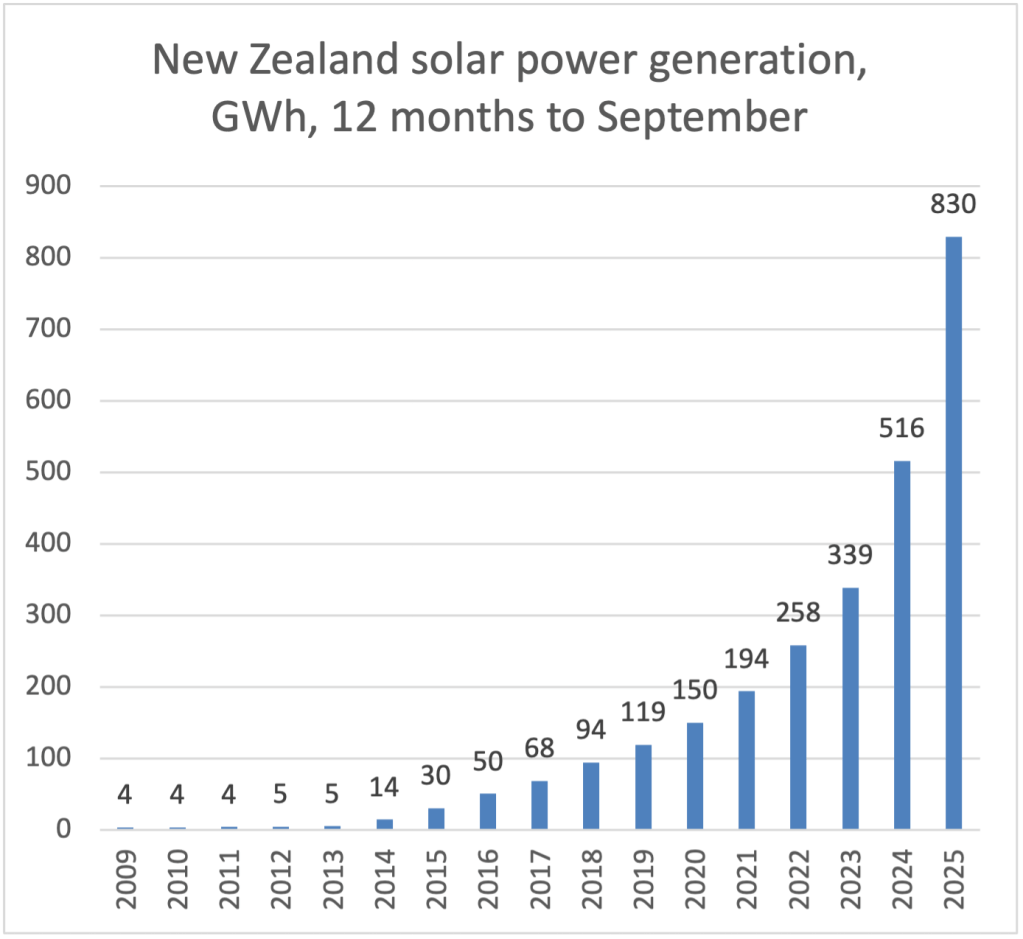

Or this one, which also went off, showing super-exponential growth of solar power in New Zealand:

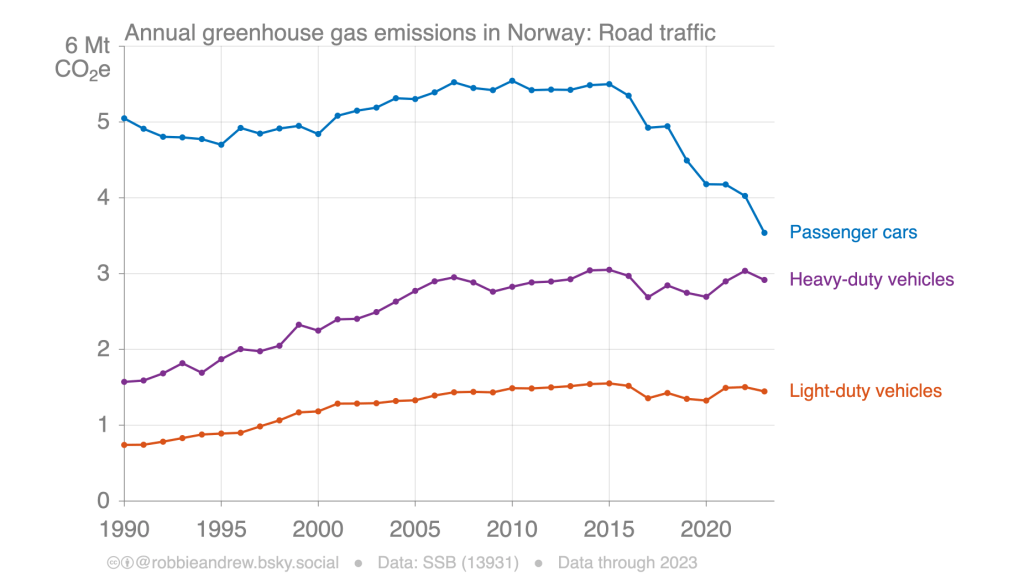

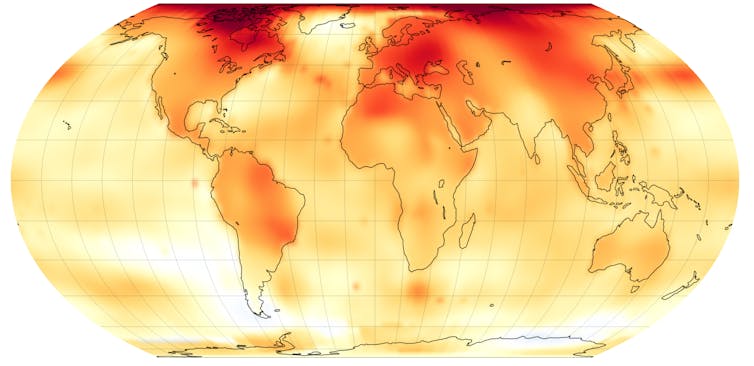

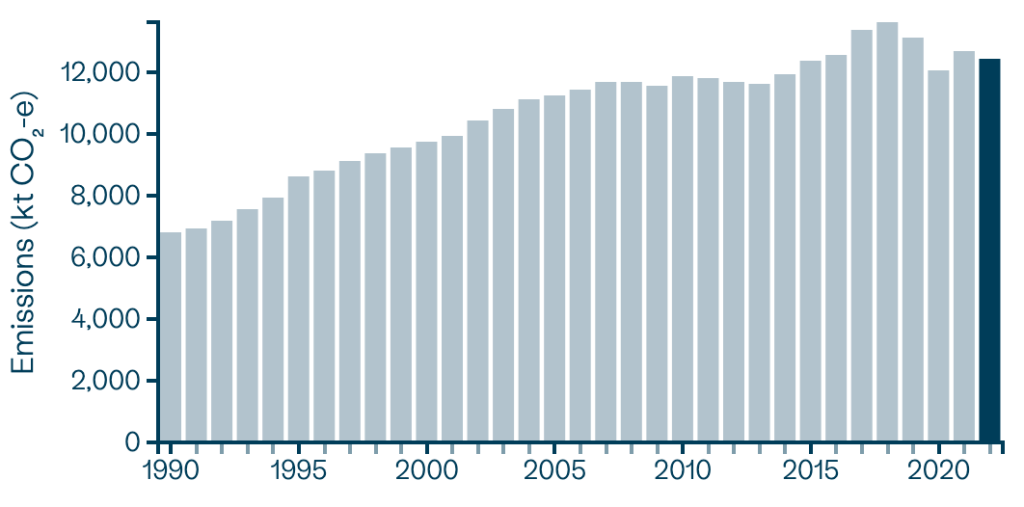

But posts showing bad news tend to do poorly:

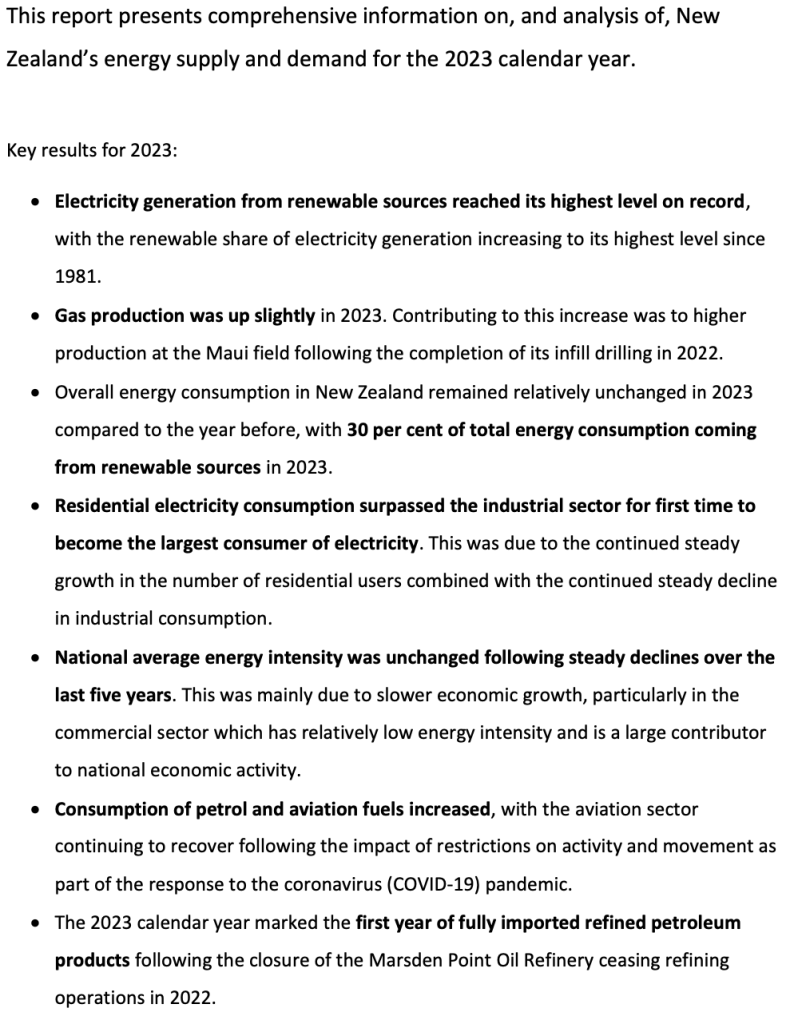

However, that last graph is perhaps the most important, for today is the last day of the first emissions budget period, which ran from 2022 to 2025. The system of emissions budgets was set up by the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act 2019, which unleashed a wave of low-carbon investment across the country. Even Fonterra, which only a couple of years earlier was still obscuring their role as the country’s largest coal burner, began to change. Officially, thanks to some dodgy accounting, we are on track to meet the first budget, although the final reckoning (including agriculture and forests) will not be in for another year.

We do, however, have nearly complete data for energy emissions. These show a dramatic change after the Zero Carbon Act changes had time to kick in:

| 2018-19 | 60.9 Mt CO2 | 2% below 2007 peak |

| 2020-21 | 59.5 Mt CO2 | –2% |

| 2022-23 | 54.0 Mt CO2 | –9% (!!!) |

| 2024-25 | 53.9 Mt CO2 | no change; progress halted |

The progress in 2022-23, the first half the budget period, is impressive. (However, 1/3 of the reduction was due to the closure of the Marsden Point oil refinery, which shouldn’t count as the emissions were shifted offshore.) Progress appears to have halted in the second half, and although climate action hasn’t completely halted, the constant barrage of anti-climate action and rhetoric from the government is having an effect.

Which brings me to my point. Top-10 lists are a year-end classic. But in this case it seems more appropriate to nominate the…

Government’s bottom 10 climate actions of 2025

And how hard it is to choose. I’ll start by ruling out things that are merely said, like Shane Jones’s comment on anti-coal protesters that “The high tide mark of this unicorn kissing green drivel is over,” or two out of three Government coalition partners proposing to leave the Paris Agreement. It’s hard to draw the line, though, as words have an effect too – like the Climate Change Minister telling Federated Farmers that we have no legal obligation or liability to meet the Paris targets. I’m looking at real actions that will likely lead to the most actual damage, either direct (by increasing pollution) or indirect (by fostering division). (A few sins of omission will also crop up.)

10. ETS failure. The Government may say the ETS is its main tool to control emissions, but the market says otherwise – the price of carbon credits has dropped from a high of $87 in September 2022 to $37 now. Each Government announcement seems to result in a slump: doubling the free allocation to Reio Tinto, rejecting advice to review free allocations, uncoupling the ETS from the Paris target, cutting the number of companies that must report their emissions by 55%. Since 2012, none of the 12 ETS auctions have cleared completely; 2 have partially cleared.

9. No action on aviation emissions. The First Emissions Reduction Plan included an item to prepare a plan to decarbonise domestic aviation. (While other actions were repeated, this one was not.) There has been no work on this. Instead, the group Sustainable Action Aotearoa (set up by the ERP) has been sidelined and their work on updating our State Action Plan for the International Civil Aviation Organisation stopped.

8. The Carbon Neutral Public Sector got the chop. This one is a repeat, as National already chopped it once before, in 2009.

7. No Energy Plan. In ERP1, we were promised a comprehensive Energy Plan by December 2024. There is no sign of it yet, only some brief, piecemeal documents and a series of anti-climate energy initiatives. (LNG terminal, anyone?)

6. Offshore oil & gas exploration to be restarted, with a $200 million public sweetener and going gentler on the industry’s clean-up requirements.

5. Overseas climate financing, largely to the Pacific, which was $450 million in 2024, was cut to $100 million.

4. An end to bipartisanship. In major changes announced for the formerly bipartisan Zero Carbon Act, the Climate Change Commission will no longer provide advice on Emissions Reduction Plans, and the Government will be able to amend Plans at any time without consultation. Between the loss of bipartisanship and the erosion of the system of checks, balances, and communication between the Commission, Government, and public, the Act is under threat.

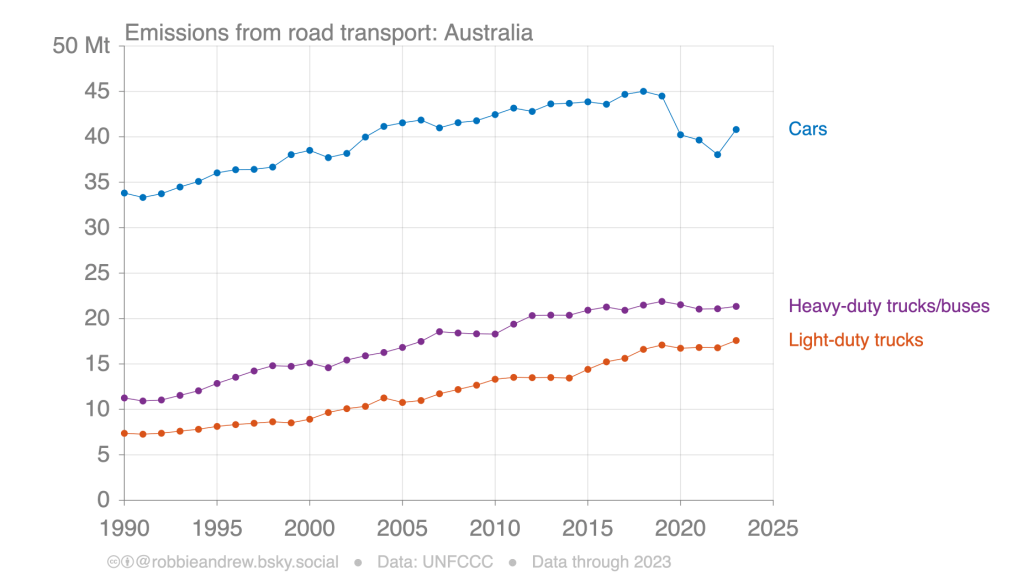

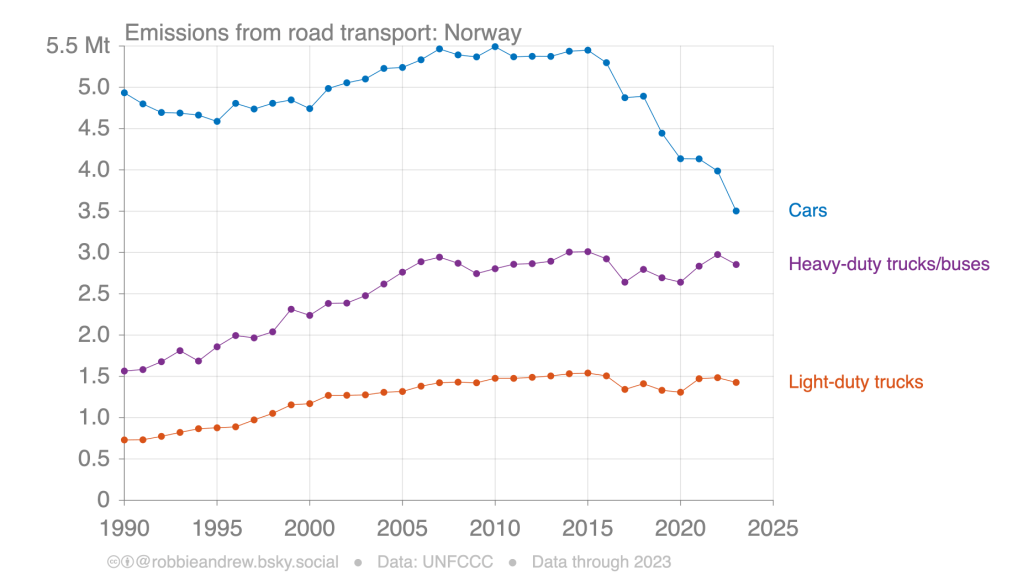

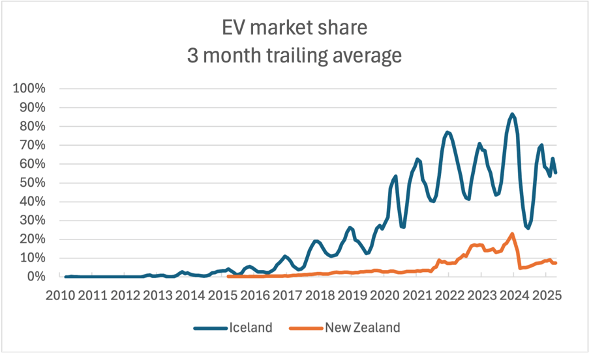

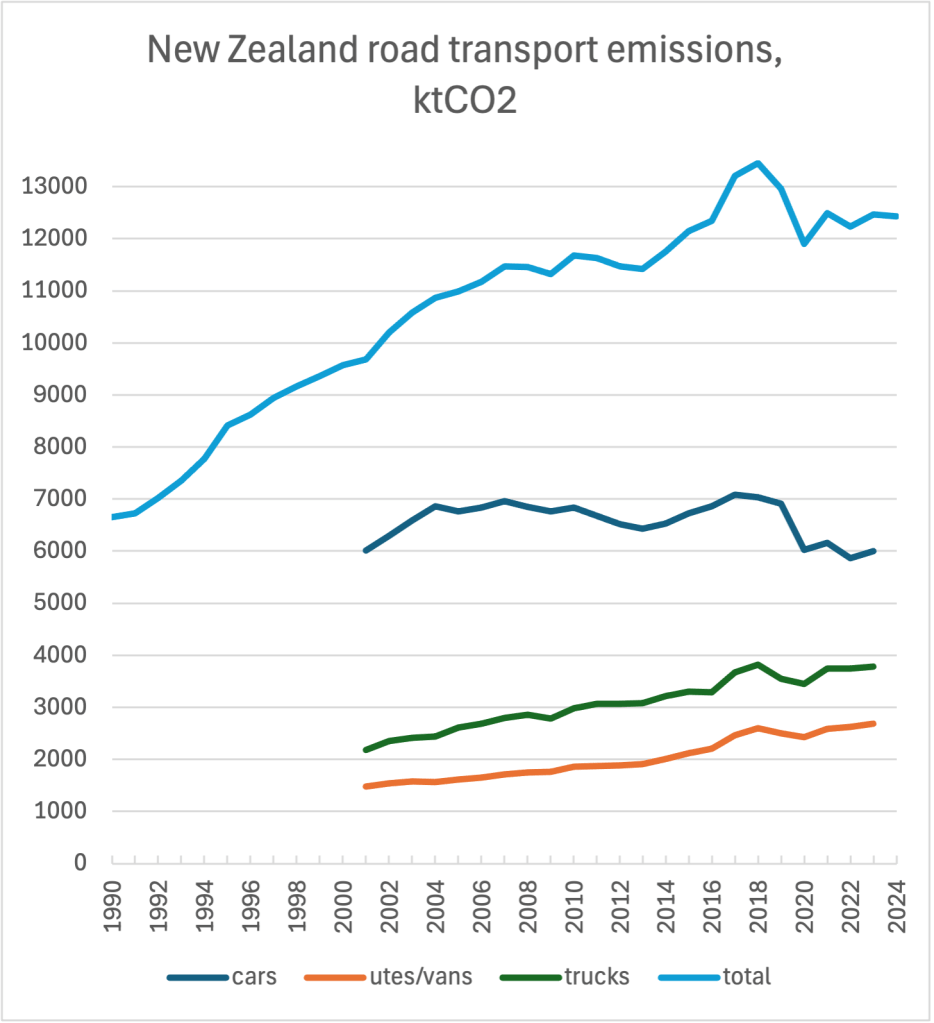

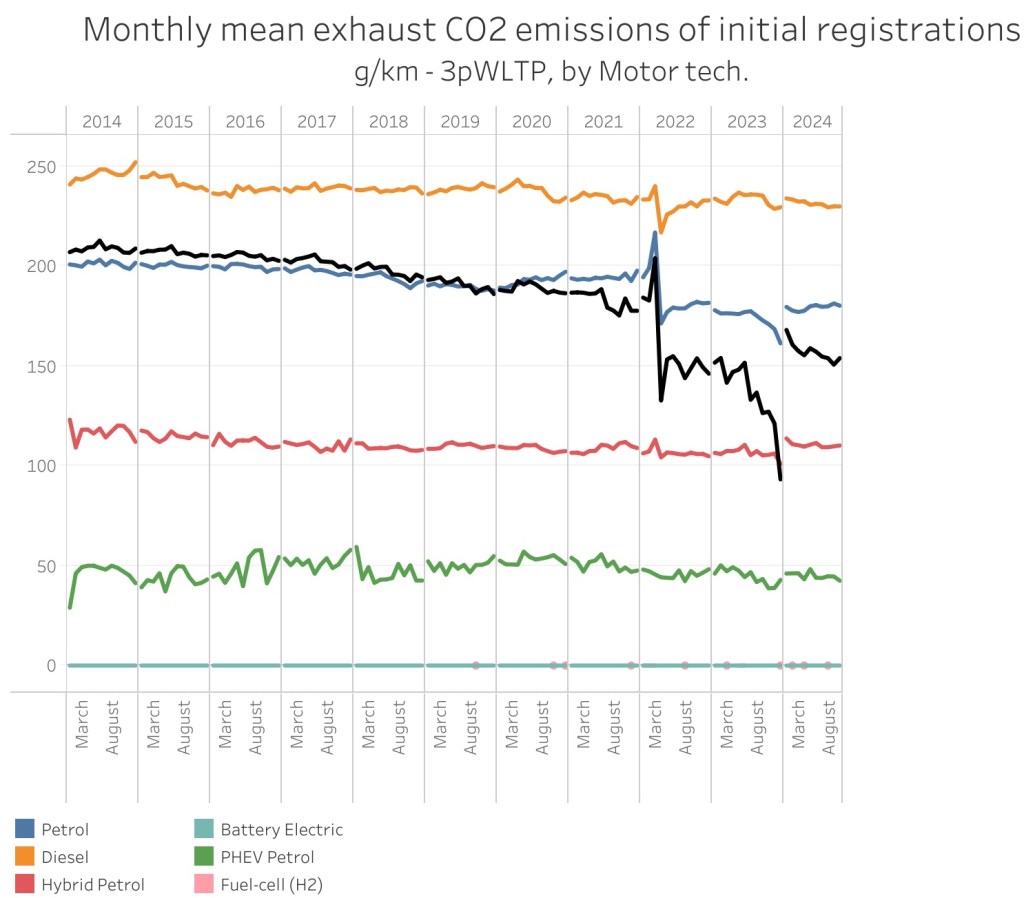

3. Clean Vehicle Standard gutted. This one is close to my heart as I have been following this story at least since the incoming John Key government killed fuel economy standards for the first time, in 2009. We all know how the feebate was boosted into a fake culture war, and how the Standards themselves were then drastically weakened for future years. Now the penalties that car importers must pay for not meeting the standards have themselves been cut by 80% for 2026 & 2027 – the same method used by Donald Trump to get rid of US standards. The move was supported by patsy modelling from the Ministry, which claimed the move would have almost no effect on emissions. The industry had taken no action at all to try and meet the targets, instead seeing a way forward through lobbying. It appears that any pro-climate faction within the industry bodies has been defeated, and the hand of the industry to dictate its own regulations strengthened. The extra costs in fuel and climate damage run to many hundreds of millions of dollars. EV sales, which fell 70% in 2024, are stagnant, and road transport emissions (which fell after Covid, partly as a result of working from home) are tracking up again.

2. No action on CO2 target. The Climate Commission advised the Government to strengthen the 2050 CO2 target to net –20 MtCO2 per year, including international aviation and shipping. All advice was rejected.

And the very bottom Government climate action of 2025 is…

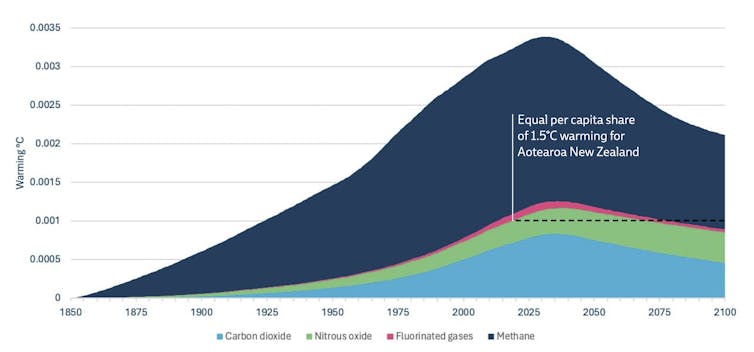

1. 2050 target weakened. The Zero Carbon Act was amended under urgency with no public input – even the public gallery was closed – to weaken the 2050 methane target under a spurious “no additional warming” excuse. As Christina Hood has written, this increases our total emissions by the equivalent of 500 years of operation of the Huntly power station and takes our 2050 target nearly back to 2011 levels of ambition.

Look at that, out of numbers already! I didn’t even have time to discuss the ongoing saga over the lip service paid to our 2030 Paris Agreement target, or over our new 2035 target which fails on multiple levels.

I may be writing from Rodney, but I live in Manawatū, where our property has just suffered its most catastrophic wind damage in at least three decades. Quoted in the Otago Daily Times about the catastrophic wind storm that swept Southland and South Otago on 23 October, Dr Nathan Melia said that weather and climate models struggle to predict such events, but that “studies of European wind storms indicate that climate change will increase the frequency of strong jets.”

I’m sorry I don’t have more good news for you to round out 2025. I will leave the last work to James Renwick, quoted in the above ODT article:

Asked if he can think of anything positive New Zealand is doing about climate change, anything to feel proud of, Victoria University of Wellington climate scientist Prof James Renwick looks bemused.

“As a former climate change commissioner, and an academic in the field, I can’t really.

“We were doing some great things a few years ago, but the current government has pulled back on the good things the previous government set up. And now they’re gradually undermining the commission and the Zero Carbon Act, and the agriculture sector is getting an absolute free ride. But they’re spending, what, $50 billion on new roads?”