by Robert McLachlan

[This is my personal submission to the Draft Government Policy Statement on land transport. Submissions close at noon on Tuesday 2 April, 2024.]

In the Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP1), transport emissions fall 41% by 2035. As the Ministry of Transport says, “Achieving this will reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and give us a more sustainable, inclusive, safe and accessible transport system that better supports economic activity and community life.” There is plenty of detail in the plan:

The plan is supported by four specific transport targets:

Target 1 – Reduce total kilometres travelled by the light fleet by 20 per cent by 2035 through improved urban form and providing better travel options, particularly in our largest cities.

Target 2 – Increase zero-emissions vehicles to 30 per cent of the light fleet by 2035.

Target 3 – Reduce emissions from freight transport by 35 per cent by 2035.

Target 4 – Reduce the emissions intensity of transport fuel by 10 per cent by 2035.

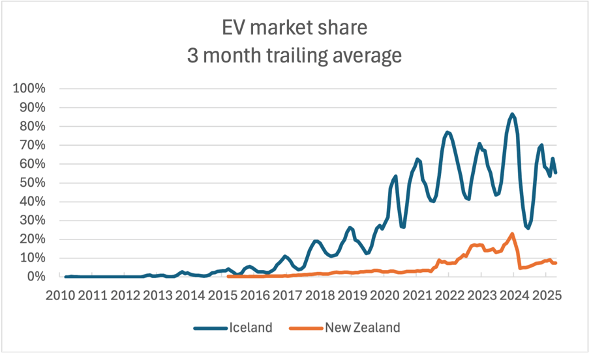

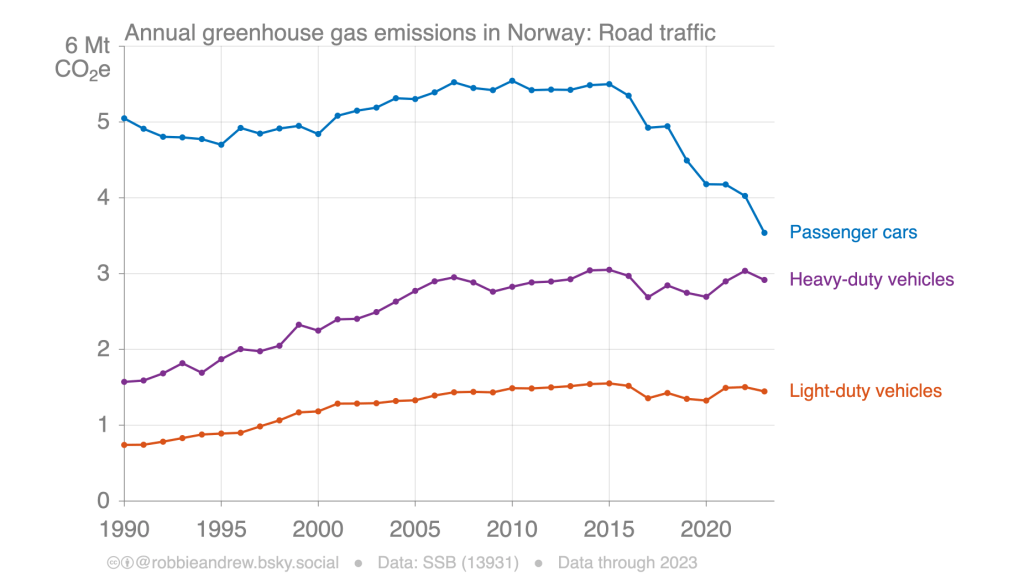

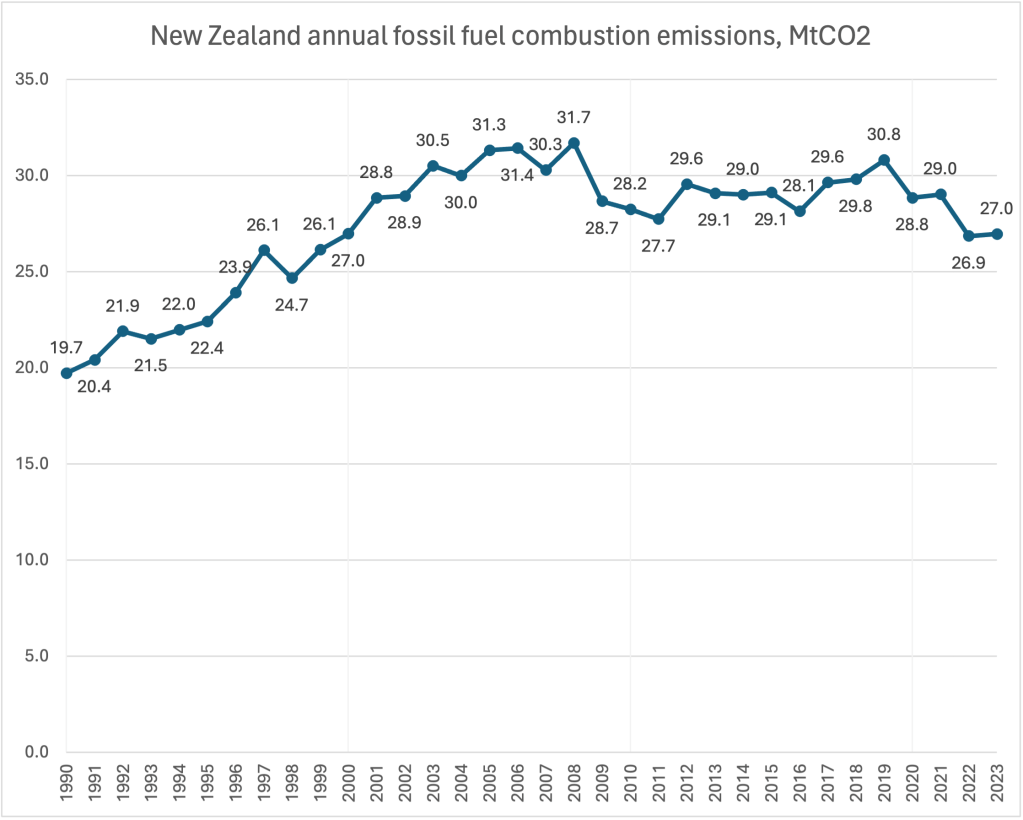

Targets 1 and 3 are wrecked by the Draft GPS, while Target 4 is already suspended. Target 2 is also threatened by related government actions to slow the uptake of EVs and other low-emission vehicles: cancelling the CCD, imposing high RUCs on EVs (a world first), proposing to weaken the CCS, and proposing to replace fuel tax by RUCs based on distance and weight.[1] The Ministry advise that the first two of these alone may limit EV share of the light vehicle fleet to 7% by 2030 (and 23% market share)[2], vs. 12.5% in the Climate Change Commission’s Demonstration Path (and 64% market share), putting the 2035 target at risk. However, the Ministry’s model involves 22,000 EV sales in 2024. In fact there were only about 1,700 sales in the first quarter.

The ERP1 for transport is not rocket science and should not be at all controversial. Internationally, all transport climate plans include the basic elements of fuel standards, mode shift, public transport planning. The IPCC in their summary of evidence say the same thing. The debate is over the mixture of fees, incentives, regulations, and bans, not over the direction of travel. The Draft GPS would wreck this plan. Spending on walking, cycling, and public transport would reduce and become highly constrained. Spending on rail infrastructure would reduce drastically, which could render the national rail network non-viable. That in turn wrecks the New Zealand Rail Plan, intended to increase the proportion of heavy freight carried by rail by building high-tech truck/rail freight hubs and new rail ferries.

Dropping climate from the GPS drops it from NZTA, currently the lead agency charged with delivering emissions reductions from transport. What could replace it? The government is committed to meeting the emissions budgets, but have not yet released much detail about how they plan to do that, other than that the ETS will be the main tool.

But it is well known that carbon charges are not an effective way to reduce transport emissions. At current prices the ETS adds 15 cents per litre to the price of petrol, or $15/1000 km. The RUC rate for light vehicles is $76/1000 km. The carbon price would have to increase by a factor of five just to match that, which is unthinkable – it would destroy all other exposed sectors.

This issue has been covered extremely thoroughly in the international literature. In 2022, I co-authored a review with David Hall on “Why emissions pricing can’t do it alone”[3]. The Climate Change Commission identified ten types of barriers to a low-emission transition; tellingly, transport is the only sector for which they proposed specific fixes for all ten barriers. Nearly all of them are under attack.

So it is really flying in the face of evidence think that the ETS can be our main climate tool, particularly for transport. Details are lacking – Minister of Climate Change Simon Watts will only say that work on the second Emissions Reduction Plan (2026-2030) is under way. Analyst Christina Hood has repeatedly detailed how the ETS will struggle to deliver even under present conditions[4].

Emissions reductions first entered the GPS in 2015, under John Key. It was raised to a strategic priority in 2018 and 2021, but now it is proposed to be dropped. Presumably, all work streams in NZTA related to emissions reduction will be stopped and all work teams dissolved. So, despite all the other alarming and potentially disastrous parts of the Draft GPS, this one is the worst.

Section 5ZI(3) of the Climate Change Response Act 2002 states that

The Minister may, at any time, amend the plan and supporting policies and strategies to maintain their currency, (a) using the same process as required for preparing the plan; or (b)in the case of a minor or technical change, without repeating the process used for preparing the plan.

But the Draft GPS states, in contrast, that

Following the general election and a change of government in late 2023, the intended emissions reduction policies foreshadowed by the previous Government are being reassessed. For this reason, GPS 2024 has not undertaken the alignment exercise as anticipated in ERP1. The Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) is the Government’s key tool to reduce emissions. In addition to the ETS, matters relating to climate change/emissions reduction issues are being worked through and will be addressed during development of the second Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP2).

Thus both the Draft GPS and the decision to not perform the alignment exercise are in violation of the Climate Change Response Act 2002. Note that the relevant “plan” referred to in section 5ZI(3) in this case is ERP1, not ERP2. In addition, many of the activities needed to support the 2nd and 3rd carbon budgets need to be undertaken in the first budget period.

Slower transport emissions reductions from existing policies mean that other policies will need to be developed to replace them. I am skeptical that the two that have been announced – higher carbon prices and faster EV charger rollout – can make up the difference. But at the very least the modelling and policy advice to support this approach should be published. To put it another way, the climate plan and the transport plan should be prepared together. But they have not been prepared together in what appears to be a deliberate strategy.

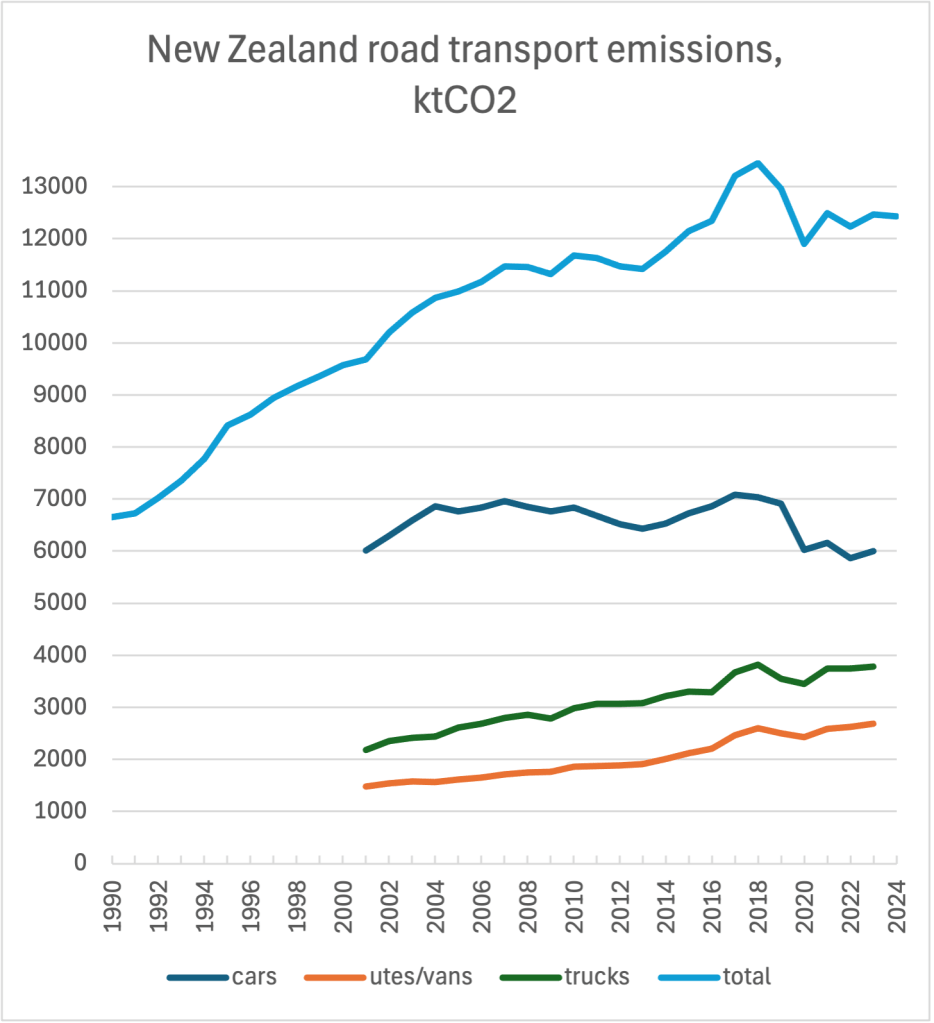

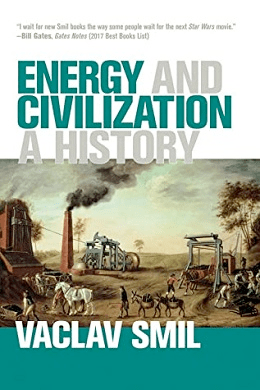

Another possibility is transport emissions will be allowed to decrease more slowly that previously intended and that other sectors will make up the difference. But transport is so large a share of emissions that it is hard to know where the other savings could come from. Three other large sectors are agriculture, industry, and trees. The first two may struggle to deliver greater cuts, while trees are already performing a far greater share of net emissions reductions than in any other developed country and are also facing policy challenges and risk transferring climate obligations to future budget periods.

To sum up, the Draft GPS constitutes climate denial.

Recommendations

R1. Perform the alignment exercise required of the GPS by ERP1.

R2. As the proposed changes to ERP1 are neither minor nor technical in nature, but strike directly at its heart, revise ERP1 using the process required by the Climate Change Response Act.

R3. Publish the legal advice received regarding R1 and R2 above.

R4. Reinstate emissions reduction as a strategic priority of the GPS.

[1] https://www.thepost.co.nz/nz-news/350179050/casualties-governments-declaration-war-evs

[2] Departmental Report to the Transport and Infrastructure Committee, RUC Amendment Bill, https://www.parliament.nz/resource/en-NZ/54SCTIN_ADV_60f18385-f31e-4c3e-1dba-08dc38a90c66_TIN1082/e69f6e2b63ae81e98f300a8d3cc146de8b21ae76

[3] https://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/pq/article/view/7496

[4] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/nz-ets-review-zero-carbon-act-theory-vs-reality-christina-hood/?trackingId=DtF8IukNSzW5egD9Mc2POg%3D%3D