By Robert McLachlan

In the Manawatū region of New Zealand where I live, the Horizons Regional Council plans for climate change impacts under the high-emission “RCP8.5” scenario. This is a scenario in which no attempts are made to reduce emissions – the track we were on for decades. In this scenario, emissions triple by 2100 and coal burning expands by a factor of six.

This is now considered highly unlikely. So why is it still used for planning?

The Ministry for the Environment recommends

using the middle-of-the-road scenario (RCP4.5) and the fossil-fuel intensive development scenario (RCP8.5), and screening hazard and risk assessments for longer-term coastal impacts up to 2130 (RCP8.5).

RCP4.5 reflects moderate emissions and implementation of current global emissions reduction policy settings. It represents limiting the rise in global air temperature to 2.7°C by 2100.

RCP8.5 broadly aligns with emissions-reduction practice over the past few decades. It reflects high emissions, limited mitigation measures and no global emissions reduction policy settings. This scenario represents a rise in global air temperature to 4.4°C by 2100. RCP8.5 enables local government to understand the full extent of possible climate risk. It is particularly important for developments with a long timeframe (more than 100 years), especially for climate-sensitive projects and coastal planning activities, due to the very long time-lag (from decades to centuries) between sea level rising and seeing the effects on developments.

Ministry for the Environment. 2022. National adaptation plan and emissions reduction plan. https://environment.govt.nz/assets/publications/national-adaptation-plan-and-emissions-reduction-plan-guidance-note.pdf

RCP8.5 is relevant not just as a worst-case scenario of emissions. The key point is that it gives an idea of a bad-case outcome for the climate response even under moderate emissions. For that reason, only RCP8.5 should be used for planning; RCP4.5 still allows a completely unacceptable level of risk.

Climate change predictions are highly uncertain. One measure is the “Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity”, the increase in temperature in response to a doubling of CO2, after short- and medium-term feedbacks have entered equilibrium. (“Medium-term” means decades to a few centuries). This has long been estimated at 2–4.5 ºC, with an average of 3 ºC. We are currently at just over half a doubling, resulting in 1.3 ºC of warming, although not all those feedbacks have yet run to equilibrium.

2–4.5 ºC is a wide range, and that’s only the “most likely” values – a 66% probability. If the sensitivity is actually on the high side, then even moderate emissions will lead to much greater impacts.

There are two fundamental reasons why the uncertainty is so large and has proven difficult to reduce.

First, there are many climate feedbacks. Some lead to more warming and some to cooling. Each is hard to predict accurately because of the long time scales and complicated interactions of the atmosphere and ocean.

Combining effects of the same sign needn’t increase uncertainty:

A = 10 ± 1 (10% uncertainty)

B = 10 ± 1 (10% uncertainty)

A + B = 20 ± 2 (10% uncertainty)

But combining effects of opposite sign always increases uncertainty:

A = 10 ± 1 (10% uncertainty)

B = –5 ± 0.5 (10% uncertainty)

A + B = 5 ± 1.5 (30% uncertainty)

Secondly, the uncertainty is worse on the high side:

Here the most likely response is 3 ºC, but very large values (6 ºC or even higher) are possible. In the most recent IPCC report (AR6) the most likely range was reduced somewhat, to 2.5 ºC–4 ºC. However, this was due in part to discarding a number of “hot models” that showed higher sensitivity. (In those models, forecasts of less clouds meant less sunlight reflected directly back to space, and hence more warming.) And that was done for a good reason, namely that the mid-range models fit the observed warming extremely well:

The takeaway message is that even under moderate emissions, there is still a pretty decent chance of catastrophe.

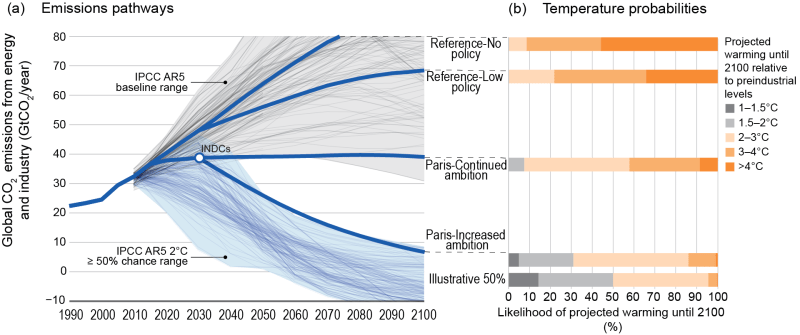

Here the “no policy” scenario (RCP8.5) gives a 90% chance of more than 3 ºC of warming by 2100. But even “Paris–continued ambition” (which assumes that all countries in the world achieve their 2030 targets and continue decarbonising at the same rate) has a 42% chance of exceeding 3 ºC. Only “Increased ambition”, in which decarbonisation accelerates greatly after 2030, gives a decent 14% chance of avoiding 3 ºC. That’s an “extreme climate change” scenario, with up to 60% of the global population at risk of starvation.

Risk is a funny thing. For aircraft, we think a 1-in-10 million chance of a crash is an acceptable level of risk. If a crash is linked to a design flaw, the entire global fleet of that model is grounded indefinitely. For flooding, we’ve settled on a 1-in-500 annual risk of catastrophic urban flooding in any given location. (In Palmerston North, stop banks were upgraded to that level just in time to survive the 2004 floods.) For climate change, a 50-50 risk of complete annihilation is met with “that’s the best we can do”.