by Heidi O’Callahan

[The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade is undertaking its triennial Strategic Foreign Policy Assessment. The Ministry writes: “The Assessment will examine the international context New Zealand will navigate in the decade to 2036, and what this means for us. The Assessment will consider the most important changes and drivers we see happening in the world, what they mean for New Zealand, what those changes mean for our relationships, and what they mean for our region — the Pacific and the Indo-Pacific.” Heidi O’Callahan’s submission is below. She would love to read other people’s submissions that tackle other (climate-exacerbated) topics, like overfishing, war, peacekeeping, humane treatment of refugees, terrorism, the scam economies and cyber security.

Submissions can be made at https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/J7J8P9V. Submissions close at 5pm on 24 December 2025.]

What are the big international issues you think New Zealand will have to navigate over the next 10 years, and what are the opportunities you think New Zealand can pursue?

The big international problems we must navigate are biodiversity loss and climate change,

as well as the poverty, inequity, migration, societal breakdown and geopolitical instability

exacerbated by these problems. To navigate these issues successfully requires accepting

the root cause: an unsustainable economic paradigm of exploitation centred on the pursuit of

economic growth.

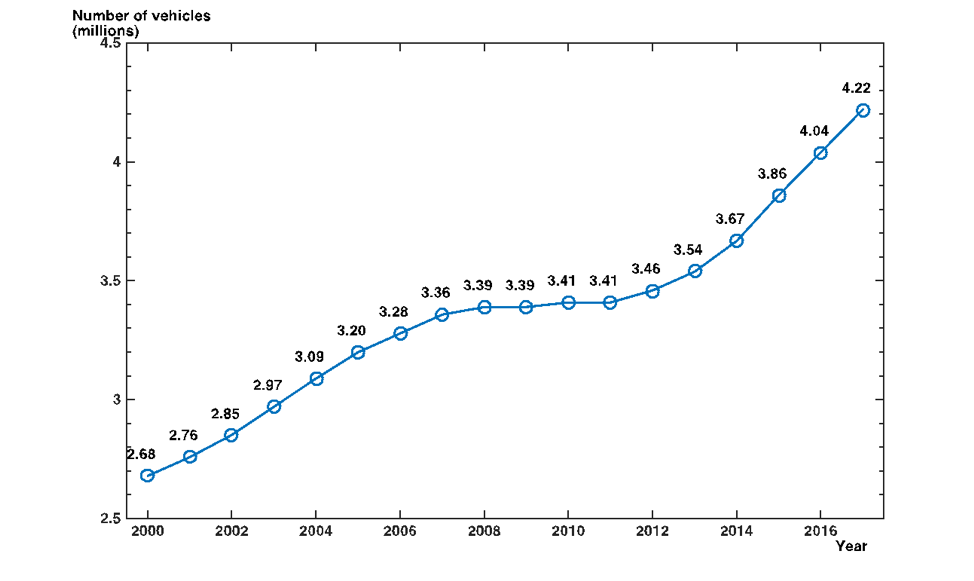

Above all, our economy needs to operate within planetary limits; it must become more

circular, socially-positive, and ecologically regenerative. Our best opportunities for

international trade lie in low-carbon, high-value intellectual innovation. The current industries

of bulk commodities (timber, milk products, meat, etc) and international tourism must be

scaled back significantly. The scale of these industries cannot be justified on a climate basis,

and their pollution and transport impacts are directly damaging to New Zealanders’ health,

accessibility and freedoms.

What do you consider New Zealand’s foreign policy needs to do to protect and advance our interests in the world over the next 10 years?

Our government needs to act domestically to protect and advance our interests, if our

foreign policy is to have a chance of helping us on the international front. We are currently

witnessing the opposite; the government is introducing policy and legislation that is directly

undermining our safety and wellbeing. This is happening across all spheres: Te Tiriti,

transport, agriculture, education, health, climate, housing and social wellbeing are examples.

In climate alone, the government has 1) unethically scrapped policies designed to reduce

emissions, 2) reduced the climate targets on the basis of no evidence, 3) decided against

bringing agriculture into the ETS and 4) indicated they will baulk at paying the bill for

international credits to cover emissions that such a climate-ignorant set of actions creates

(despite buying credits being the centrepiece of the National Party’s otherwise non-existent

climate policy.)

MFAT cannot operate with any integrity on the international stage alongside such appalling

government backsliding. So, while New Zealand’s foreign policy needs to support

international climate regulations and rules that force wealthier countries like us to reduce

emissions rapidly and pay for our past damage, it is hard for MFAT staff to be taken seriously

when representing a hypocritical government.

Nor will MFAT succeed at advancing our economic interests or pursuing opportunities; the

government’s climate denial will exclude us from markets and keep us out of key

international decision-making.

It’s not just in climate we are becoming a laughing stock. The GPS on Transport attracted

derision and ridicule from international experts. The UN Committee for the Elimination of

Racial Discrimination highlighted how quickly New Zealand is going backwards under this

racist government.

New Zealand’s foreign policy should advance real climate justice, climate action, the

commitment to international agreements on improving transport safety, reducing racial,

gender and age discrimination, the pursuit of improving the wellbeing of people in all

countries (especially indigenous people, and the educational and health opportunities for

girls and women), the promotion of sustainable practices and ecological regeneration, and

above all, the dismantling of the economic paradigm that has led to the destruction of water,

soil, air, natural and human resources.

But to pursue advancing these issues, diplomats should be able to draw on robust examples

of domestic New Zealand practices, with truth and integrity. Currently, they cannot.

For you, your community, organisation or business: What matters most in the world beyond New Zealand? What places and international relationships matter most? What do you think are New Zealand’s greatest strengths and weaknesses in our international engagement?

We should pursue strong and respectful relationships with our Pacific neighbours.

One important matter “in the world beyond New Zealand” is reducing hypermobility. The

majority of people in the world have never set foot in an aeroplane. Yet a small minority

continue to fly, with enormous climate impact, and we are all subsidising them to do so.

Flying is one of the most inequitable and destructive activities humans can indulge in. Our

foreign policy should seek international mechanisms and agreements to achieve substantial

reductions in aviation. As a country with apparently much to lose (but also much to gain in

other ways) from reducing international aviation, New Zealand is actually in a strong position

to lead this international work, through demonstration of substantial systemic change. New

Zealand needs to shrink our international tourism industry, and take steps to prevent our

wealthy people from travelling so much. Our government must stop promoting New Zealand

as a destination, stop allowing airport expansions, introduce taxes to prevent recreational

and other avoidable flights, and support the transition to sustainable industries, including

sustainable bike-, rail-, and coach-based domestic tourism.

The international relationships that matter most are in implementing and honouring the

various UN conventions and agreements – on traffic safety, on climate, on wellbeing and

health, etc. It seems, currently, that this government is rejecting the authority of the UN,

willingly forgetting what atrocities led to the creation of the UN in the first place!

Currently, the most important international relationships my community has is with experts

from other countries to help us try to make gains in evidence-based transport, agricultural,

energy and climate policies for New Zealand. Currently, much community effort is being

spent trying to undo or mitigate aggressive and regressive government actions that have no

basis in evidence or accepted practices. It is very sad to see this waste of human toil and

effort, which could be being used to build a better New Zealand.

Also important are the relationships with international experts on democracy. New Zealand’s

poor democratic practices are stifling our progress. Deliberation and informed

decision-making are the basis of good democracy. New Zealand will not thrive and we will

not make the most of opportunities while most decisions are being made on the basis of

misinformed opinions, corporate lobbying, misguided pursuits of economic growth, and

populism.

New Zealand’s foreign policy should promote the international development of a body of

knowledge about modern democracy. Such an international resource would be useful for all

kinds of decision-making, and could help dispel the damaging myth that “one person one

vote” is a sufficient basis for democracy.

New Zealand’s greatest strength in our international engagement is the goodwill built up over

many decades by good diplomacy and leadership. While there has been a low bar for what a

“good” country should do to improve the welfare of poorer countries and to pursue

development goals, at least New Zealand often tried to be one of the more enlightened

OECD countries. Internationally, the standard must improve. Unfortunately, New Zealand is

not stepping up. The goodwill is evaporating rapidly.

Our biggest weakness in international relationships is the lack of integrity in our domestic

policies.

Do you have any other thoughts on the international context you would like the team to consider?

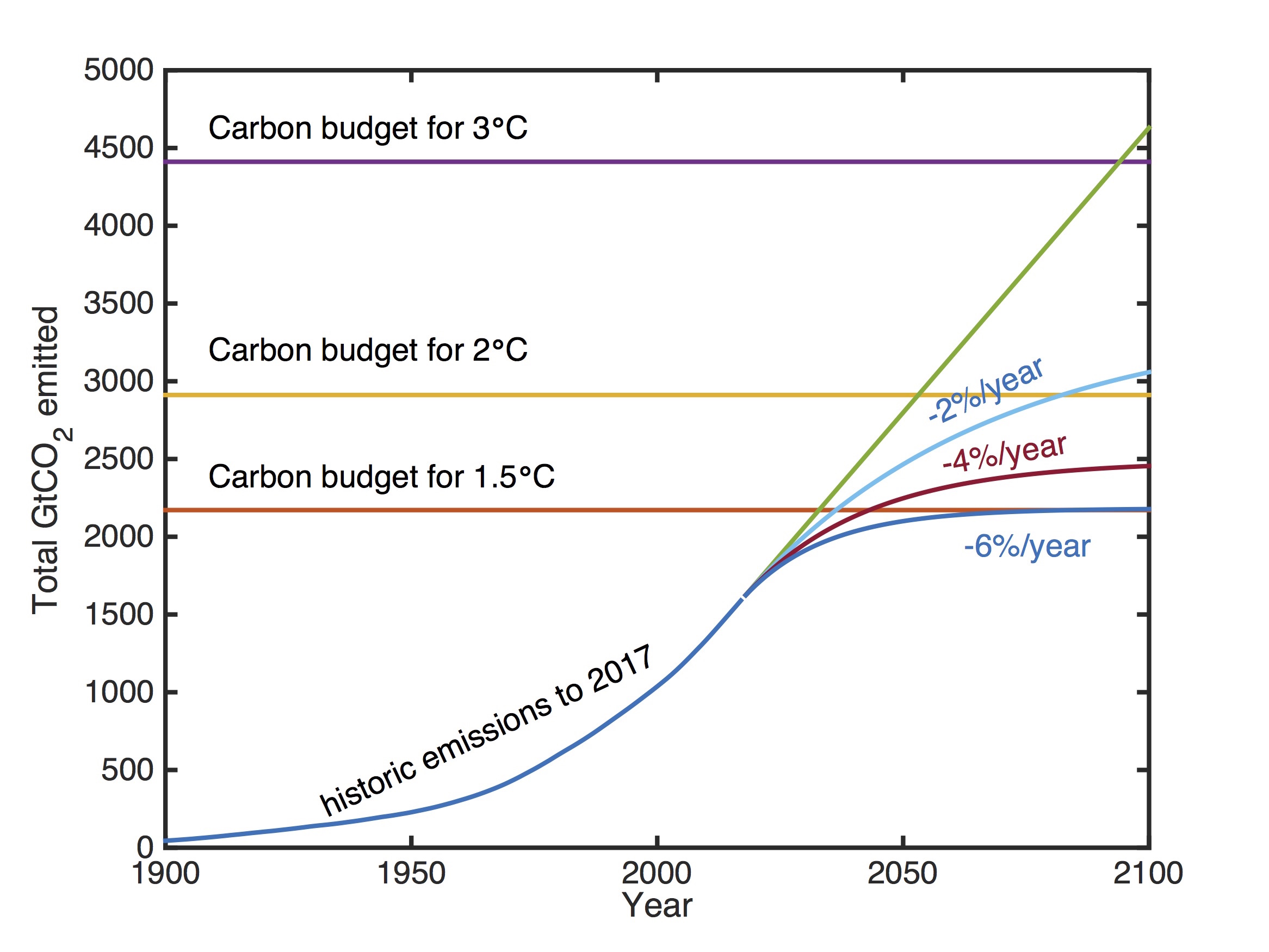

How the climate changes depends on emissions right now and over the next few years. Net

zero by 2050 is necessary but by then it will be largely irrelevant; the important point is the

emissions trajectory to get there. Bureaucrats and leaders believe they face difficult

decisions currently and rarely prioritise emissions reductions. Yet the different climate

pathways will determine the options in front of future decision-makers, who will have fewer

resources to be able to draw upon, will be functioning in more urgent circumstances, and are

likely to be working within weaker institutions.

When this is fully understood, it is clear that decision-making is unlikely to get any easier!

We must stick to ethical action that will help decision-makers in the future. We must invest to

pursue rapid and significant emissions reductions, and rapidly transform our systems so they

are low carbon. We must acknowledge that the true social cost of carbon is orders of

magnitude higher than what our ETS scheme uses; much larger than what Europe is using.

We must be responsible international neighbours, and ensure poor countries don’t have to

make decisions between climate action and social or economic health.

None of this can be delayed while climate deniers have their turn at power plays in politics.

Quality foreign policy, in the absence of quality domestic policy, is akin to “polishing a turd”.