By Robert McLachlan

On 25 June, the Government amended the Clean Vehicles Act. This was completed in a single day under urgency, so there was no opportunity for public input. On 9 July, there was a press release saying that New Zealand would now be following Australian emission standards from 2025. On 11 July, the Ministry’s advice was released, giving us a few more details.

Vehicle emissions are reported in grams of CO2 per kilometre (gCO2/km). (For petrol vehicles, 200 gCO2/km is the same as 8.6 l/100km.) Here are the new targets:

| Cars | Light commercials (vans & utes) | |||

| Previous target | New target | Previous NZ | New target | |

| 2023 | 145 | 218.3 | ||

| 2024 | 133.9 | 201.9 | ||

| 2025 | 112.6 | 112.6 | 155 | 223 |

| 2026 | 84.5 | 108 | 116.3 | 207 |

| 2027 | 63.3 | 103 | 87.2 | 175 |

| 2028 | 76 | 144 | ||

| 2029 | 65 | 131 | ||

The Minister talked to the Motor Industry Association (MIA), the Imported Motor Vehicle Industry Association (VIA), the Motor Trade Association (MTA) and the New Zealand Automobile Association (AA). We don’t have their reports, but, judging by what has been released, the Minister has accepted their reasoning at face value and rubber stamped their request. Neither Tesla nor Drive Electric (not members of the MIA) were consulted.

The Ministry report that their modelling of the emissions impact of this change has not been completed yet, but they do provide a rough estimate of an increase of emissions by 0.3–0.5 MtCO2 over 2024-2050. Another department, the Climate Impact of Policy Assessment, puts the increase at 1.2–1.9 MtCO2, but regards this as unreliable on the grounds that the previous targets were unlikely to be met – which is the car industry’s argument.

The car industry appears to take the position that they will do nothing whatsoever to respond to the targets, and just let the market take its course. Car importers would pay fines rather than try to meet the target. One key figure (which was also provided to Cabinet) is their estimate that this would add $5,500 to the price of every new light vehicle in 2027.

The fines are set at $45/gCO2, so the MIA are saying they’ll miss the targets by 122 gCO2 on average. The target for all light vehicles is 71 gCO2/km, so they’re saying they expect to sell vehicles averaging 193 gCO2/km in 2027, or nearly triple the target. That level (193 gCO2/km) is what we had already reached in 2021, before the introduction of the feebate and fuel efficiency standards. In 2022 the average was 167g; in 2023, 145g.

These industry and ministry figures look like nonsense, so let’s do a back-of-the-envelope calculation. Assuming no change in overall levels of sales, and that the targets are met, the annual extra emissions from vehicles sold in 2025 will be 46,000 tCO2; in 2026, 132,000 tCO2; in 2027, 120,000 tCO2. Over the 20 year life of the vehicles, the extra emissions from sales in these three years alone are 7.14 MtCO2.

That’s all assuming the targets are met. The industry says they won’t be. But one thing we did learn from the feebate experience is that both the industry and the car buying public are incredibly responsive to signals. Under the previous government, the signal was that it’s time to get serious about cutting emissions. The price signal (the rebate) was only part of that. EV sales vastly exceeded expectations, and the industry delivered. After the election, the signaling changed; the only electric ute on the market was withdrawn less than a week later.

Source: Ministry of Transport. The Clean Car Discount (feebate) was introduced progressively in July 2021 and April 2022, and cancelled in January 2024. Chart includes both new and newly imported used vehicles.

Second, missing the targets still achieves something. Fines are a deterrent and a signal to the industry. If they’re added to the price of higher-emitting vehicles, those sales will slow. Even for utes, that’s not the end of the world, it just means a slower replacement cycle until better vehicles are available. This will still prevent new, high-emission models entering the country and sticking around for decades.

There is one issue, though, which is that the fines, at $45/g, are low by international standards. They were set low because at that time, the intention was that the feebate would be doing most of the work and the Standards were mostly a backstop. In Australia, whose standards we are now adopting, the fines are $111/g, and in Europe, $170/g. (In Europe, where emissions in 2021 were already 40% below ours, not a single car company has had to pay fines for missing the targets.) Australia and Europe have extensive systems of incentives in place, which helps. New Zealand importers also have heaps of cheap credits available from overachieving in 2023 that (in another change) can now be used up until 2027.

When the Minister of Climate Change was asked about the impact on emissions, he said that “Clean car standards … have quite an insignificant impact in regards to overall emissions targets”. The relevant number to compare to here is not total emissions, but the required annual emissions cuts as we move into the late 2020s. Those are about 2 MtCO2 per year. In that context, the change due the weakening of fuel efficiency standards – 6% of so of the total effort required – is significant.

However, the Ministry has an answer there too:

In our view the proposed targets will not impact the ability for the first emissions budget (or subsequent ones) to be met. This is because transport emissions are covered by the ETS, therefore changing the Standard’s targets might change how or where emissions reductions occur from a gross perspective, but not from a net perspective.

This comes pretty close to the common argument that nothing the government or anyone else does has any impact on emissions; if I emit more, others will emit less so that the carbon budgets are met. But, they throw in an extra twist by bringing in the gross/net distinction: basically the argument is that more trees will be planted to cover the extra emissions. None of these arguments hold water, but even if we accept them at face value, actions that lead to higher emissions in one sector will definitely have an effect on those other sectors that will now have to make up the difference. For example, through a higher carbon price. However, it appears that this effect was not considered.

The new targets do get tighter over time, particularly in 2028 and 2029. If those are met, we could still be on track to end fossil-fueled vehicle sales by 2035, as in Europe. (The new UK government is reinstating a 2030 end date.) But there are two caveats. First, Australia has an election next year. The opposition could easily make emissions standards an issue, as they tried unsuccessfully to do in the last election (“Ute tax!”). A change of government could see the Australian standards weakened, as has happened here. Second, our own new standards will be reviewed again in 2026. On present performance, the MIA would only need a quiet word in the Minister’s ear to wind back the standards.

The purpose of a fuel efficiency standard is to radically change the make-up of the fleet as quickly as possible. There do have to be changes. But the whole tenor of the Ministry’s advice is that no one should have to change or pay any more, the overriding goal is that “vehicle affordability is maintained and the mix of vehicles imported meets the needs of New Zealanders.”

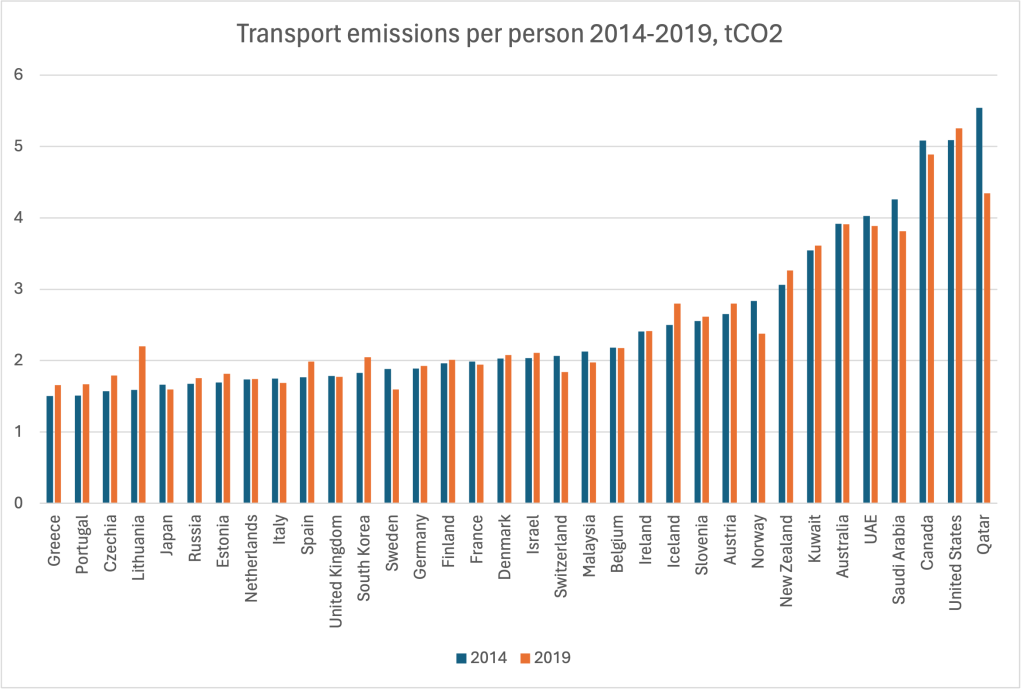

Reducing transport emissions is difficult, and it is something that many countries struggle with. But some countries are trying and are starting to see results.

Source: Our World in Data. Sweden has a target reaching of 0.6 tCO2/p in 2030.

Weakening fuel efficiency standards is the third of four parts of the Government’s “War on EVs“. Part 1 was ending the feebate; part 2 was the introduction of Road User Charges (RUC) for EVs, at a punishing rate. Iceland is the only other country in the world to try this, and there too sales have collapsed. Basically we are in uncharted waters. Part 3 is now done. Part 4 is still to happen: it’s the Government’s signaled intention to replace petrol tax with RUC for all vehicles. As petrol tax is currently equivalent to a carbon charge of $360/tCO2, this would amount to a hefty carbon tax cut and hence would also act to increase transport emissions. The extra cost of driving a hybrid (where sales are still holding up well) could be significant.

| Fuel consumption l/100km | Current fuel/RUC cost cents/km | Fuel/RUC cost under an RUC-only system |

| 0 (Battery electric) | 12 | 12 |

| 4 (small hybrid) | 10 | 14.5 |

| 6 (normal hybrid) | 15 | 18 |

| 8 (normal car) | 20 | 21.5 |

| 10 (large car) | 25 | 25 |

| 12 (large ute) | 30 | 28.5 |