By Robert McLachlan

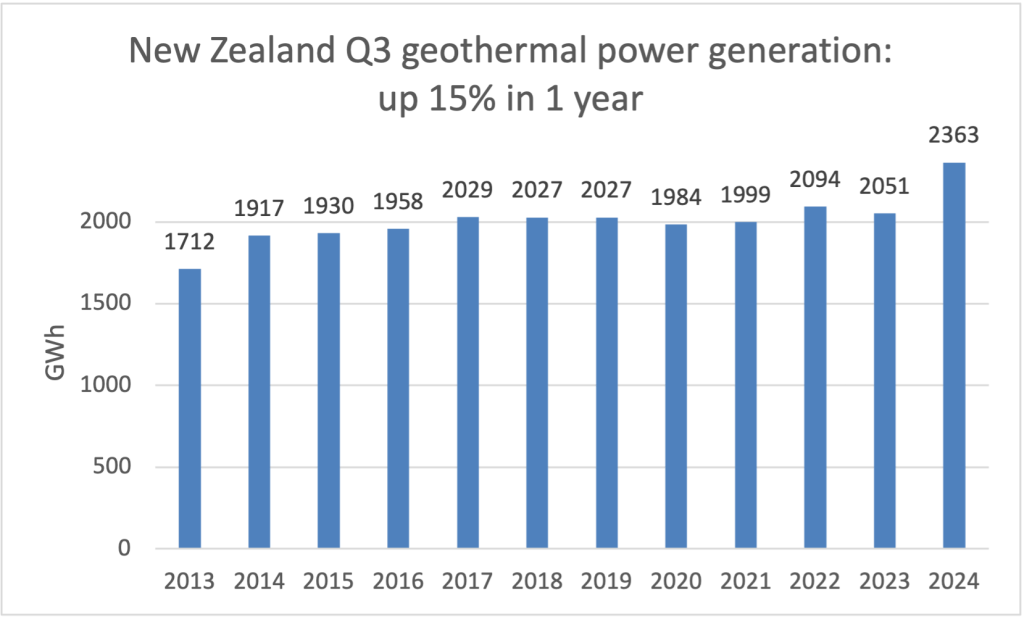

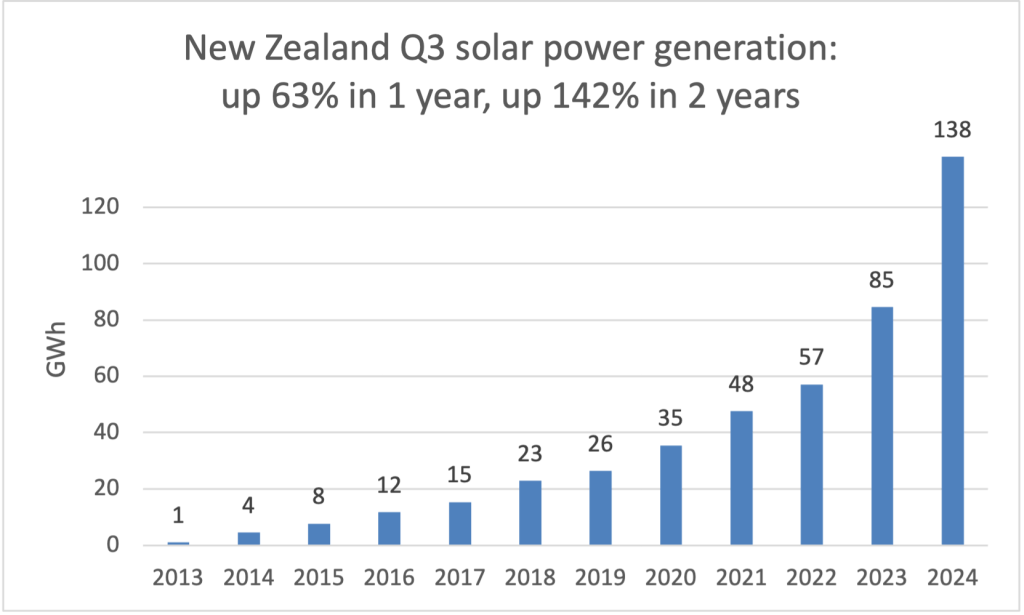

Every three months the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment puts out a useful document called the Energy Quarterly. It provides up-to-the-minute data on fossil fuel emissions, well in advance of the more detailed submissions for the UN which currently only run up to 2022. It’s where I get the data for graphs like this one:

My point is to make regular reminders that addressing climate change means phasing out fossil fuels and that we are only just starting on that task. But the details are important and interesting, too, such as the recent upswing in electricity emissions due to the record-low lake inflows. This serves as a reminder that the ‘dry year’ problem isn’t yet solved, and that without the significant new wind and geothermal plants that were completed in 2023 and 2024 we really would have had an energy crisis.

The electricity generation data in the Quarterly also shows that a long static period in New Zealand’s power generation is coming to an end. The biggest trigger for investment was the passage of the Climate Change Response (Zero Carbon) Amendment Act in 2019; projects that started construction in the following years are now operating.

However, future growth depends on anticipated future demand from climate action – phasing out fossil fuels and ‘electrifying everything’. The energy and transport sections of the final Second Emissions Reduction Plan do nothing to promote electrification, placing this recent growth at risk.

But what about the big picture on energy?

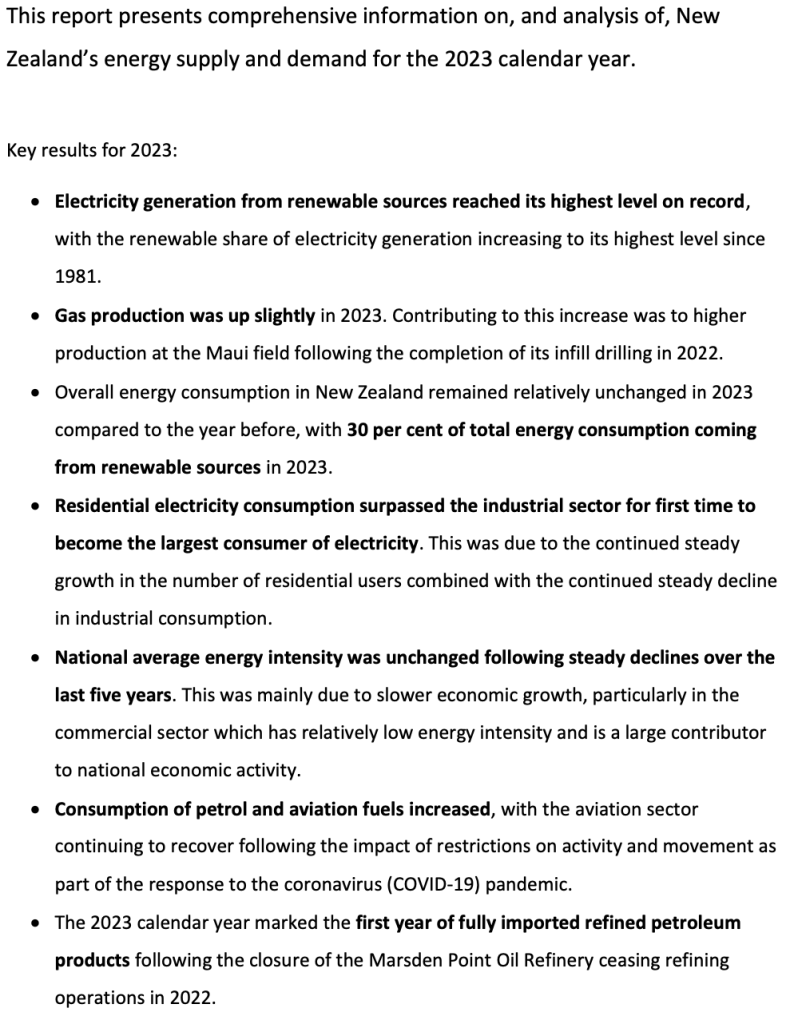

In addition to the Quarterly, MBIE produces an annual report, the latest being New Zealand Energy 2024. Here’s their summary:

The report includes many graphs, but not one showing what to me is the most striking development: total energy use has been falling for six years, and is now down nearly 10% from its peak in 2017.

Coal, gas, oil, and even renewables are all down from their peaks. Looked at per capita, the effect is even more striking:

Energy use per person has been declining fairly steadily since 2001, and is now down 28% from peak. Is twenty-two years long enough to call it a trend?

There are probably many factors at play here that would be hard to untangle. At first sight the data doesn’t fit either of the convenient narratives on energy, ‘transition’, in which modern renewable energy gradually replaces fossil, or ‘more and more‘, in which new energy sources simply add to humanity’s rapacious demands.

Most likely a combination of factors – energy efficiency, deindustrialisation, and behaviour change – are at work. Initial indications are that all three of those effects were still in play in 2024, as energy-intensive industries shut down or scaled back. When we do get started on mass electrification and serious behaviour change, the energy decline will accelerate.

I can understand consumption gas decreasing because there is less available.